Women and men in Sweden - Facts and figures 2024

- Published:

- 2024-11-05

Gender equality

Women and men must have the same power

to shape society and their own lives.

Gender equality – equality

The term gender equality is used to define the relationship between women and men. However, equality is a broader concept. It refers to parity in relations among all individuals and groups in society. Underlying this notion is the belief that all people are of equal value, regardless of sex, ethnic origin, religion or social class.

Swedish gender equality policy

The overall objective of gender equality policy is to ensure that women and men have equal power to shape society and their own lives. On this basis, the Government is working towards six sub-goals.

Equal distribution of power and influence

Women and men must have the same rights and opportunities to be active citizens and toshape the conditions for decision-making in all sectors of society.

Economic gender equality

Women and men must have the same opportunities and conditions for paid work that provide economic independence throughout life.

Gender equality in education

Women and men, girls and boys must have the same opportunities and conditions regarding education, study options and personal development.

An equal distribution of unpaid housework and provision of care work

Women and men must have the same responsibility for unpaid housework and the opportunity to give and receive care on equal terms.

Gender equality in health, care and social services

Women and men, girls and boys must have the same conditions for a good health and be offered care and social services on equal terms.

Men’s violence against women must stop

Women and men, girls and boys must have the same rights and opportunities to physical integrity.

National coordination of gender equality work

The Minister for Gender Equality coordinates the Government’s gender equality policies. All cabinet ministers are responsible for gender equality in their policy fields. The Division for Gender Equality is responsible, under the Minister for Gender Equality, for coordinating the Government’s gender equality efforts and specific gender equality initiatives. The Swedish Gender Equality Agency is an administrative authority responsible for contributing to efficient implementation of gender equality policy. The agency is tasked with follow-up, analysis, coordination, expertise and support with the aim of achieving the gender equality policy goals and they also are tasked with the distribution of government grants for gender equality projects, women's and girls' organization, and work with violence prevention.

The Equality Ombudsman supervises to ensure compliance with the Discrimination Act and the Parental Leave Act. There is a council against discrimination that can fine employers and educators if they do not honour their obligations to take preventive measures and to promote efforts to counteract discrimination on the basis of gender. The National Centre against Honour-based Violence and Oppression (NCH) at the County Administrative Board of Östergötland is tasked with contributing to strategic, preventive and knowledge-based work against honour-related violence and oppression at national, regional and local level. The National Centre for Knowledge on Men's Violence against Women (NCK) at Uppsala University and Uppsala University Hospital is tasked with raising awareness of men's violence against women, honour-related violence and oppression, and violence in same-sex relationships. Via national helplines, NCK also provides support to victims of violence who are women, men, non-binary people, and people with transgender experiences, as well as individuals exposed to honour-related violence and oppression.

Gender equality affects all areas of society

Gender mainstreaming is a political strategy to achieve gender equality in society. Gender mainstreaming is based on the understanding that gender equality is created where decisions are made, resources are allocated and norms are created. Therefore, a gender equality perspective must be incorporated into all decision-making processes by the parties that are normally involved in decision-making.

Gender equality and statistics

Women and men must be visible in the statistics

To enable this, statistics must be disaggregated by sex. Section 14 of The OffIcial Statistics Ordinance (2001:100) sets forth that offIcial statistics based on individuals should be broken down by sex unless there are specifc reasons for not doing so. Statistics Sweden has produced guidelines and support for the application of section 14, which can be downloaded from Statistics Sweden’s website. However, statistics broken down by sex alone are not sufficient for performing analyses on gender equality. For this purpose, statistics must also be used that illustrate gender equality issues in society. Statistics Sweden’s website has a thematic page (in Swedish only) with additional gender equality statistics, in addition to this publication: www.scb.se/jamstalldhet.

What does equal sex distribution mean?

There may be different definitions of what is meant by an equal sex distribution. In statistics, it is common for an equal sex distribution to mean that at least 40 percent are women and at least 40 percent are men. If a group consists of more than 60 percent women, it is female-dominated, and if it consists of more than 60 percent men it is male-dominated. This is the definition used in this publication. At the same time, one could reflect on whether the sex distribution is equal if it is always women who are close to 40 percent, and always men who are close to 60 percent, or vice versa.

Guide for readers

The information in this publication are mainly derived from productions of Statistics Sweden and other statistical agencies. The source is given next to each table/graph. In most places, the tables and graphs give absolute numbers and/or proportions (%) for various attributes among women and men.

Proportions (%) are used in two ways:

- Proportion (%) of all women and proportion (%) of all men with a certain characteristic, such as working part-time.

- Sex distribution (%) within a group, such as upper secondary school teachers.

Some area graphs reflect both the absolute numbers and sex distribution in various groups. Such graphs are shown in the section on Education. The area for each programme reflects the total number of graduates from this programme compared to other programmes.

The total figures in the tables are not always consistent with the partial figures because of rounding off. Some tables may contain rounding errors.

The Official Statistics symbol indicates statistics that are included in the official statistics.

![]()

The Labour Force Surveys (LFS) are included in the system for the official statistics. However, the tables and diagrams in this publication are specially processed data from the Labour Force Surveys and are not official statistics.

Please note that the content of the statistics may change and that they may not be comparable over time. For further information regarding comparability and other aspects of statistical quality, readers are referred to the sources indicated. See also Statistics Sweden’s website at www.scb.se.

Some of the statistics in this publication come from sample surveys. Values derived from sample surveys are estimates that are subject to some uncertainty. This uncertainty can be expressed using uncertainty figures. Uncertainty figures are not reported in this publication. Instead, they are available on Statistics Sweden’s website at www.scb.se/LE0201.

Legend:

– No observation (magnitude zero).

0 Magnitude less than half of unit.

.. Information is not available or is too uncertain to use.

. Category not applicable.

Population

The composition of the population can provide important information for interpreting statistics on the living conditions of women and men. For example, an ageing population brings about an increased need for care, which has implications in several areas for women and men.

Forty years ago, the population of Sweden was around 8.3 million, of which 4.2 million were women and 4.1 million men. Historically, population growth in Sweden has been the result of more people being born than dying, but since the middle of the 20th century, net immigration has played a greater role.

In this chapter, we describe Sweden’s current population and its composition as well as how it has changed over time

Demography - Population composition

Since 1900, Sweden's population has doubled. Throughout the 20th century, the population consisted of slightly more women than men, but in 2015, for the first time, men outnumbered women. Two years later, in 2017, we passed the 10-million mark, and by 2023 we were approximately 5.2 million women and 5.3 million men.

Population in Sweden 1900 - 2023

Annual population growth has varied over time and depends on the number of births and deaths, as well as immigration and emigration. From the beginning of the 20th century until the 1970s, population growth in Sweden was mainly due to the number of births exceeding the number of deaths. Every year, slightly fewer girls are born than boys. The number of women and men who die in a year depends largely on prior mortality and on the change in average life expectancy. Women live slightly longer on average than men.

In the mid-20th century, the number of people who immigrated increased. This was partly due to labour immigration in the 1950s and 1960s, and later to the receipt of refugees and family reunification. Today, population growth is mainly due to the number of immigrants exceeding the number of emigrants, i.e., positive net migration. Among both immigrants and emigrants, there are usually fewer women than men. As a result, net migration is usually roughly equal for women and men. However, during periods when net migration is highest, such as in the mid-2010s, the increase has tended to be greater for men than for women.

In 2023, Sweden had the lowest relative population growth since 2000, due to decreased net migration and decreased childbearing.

The 20th century has seen several major changes. Women are giving birth to fewer children on average, life expectancy has increased and Sweden has gone from being a country of emigrants to a country that receives large numbers of immigrants. It is mainly the first two factors that have changed the age structure of the population, as the proportion of children has decreased and the proportion of elderly has increased.

Population by age, 1900

Population by age, 2023

Population by Swedish/foreign background and age, 2023

| 0-19 years | 20-65 years | 66- years | ||||

| Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| Born abroad | 10 | 10 | 27 | 27 | 15 | 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Living in Sweden 0–4 years1 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Living in Sweden 5– years1 | 6 | 6 | 22 | 22 | 14 | 13 |

| Born in Sweden | 90 | 90 | 73 | 73 | 85 | 86 |

| with both parents born abroad |

17 | 17 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| with one parent born abroad |

13 | 13 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 4 |

| with both parents born in Sweden |

61 | 61 | 61 | 61 | 81 | 81 |

| Total percent | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Number | 1 173 | 1 243 | 2 966 | 3 105 | 1 100 | 964 |

Households

About one fifth of households in Sweden consist of cohabiting persons with children, and slightly less than a quarter consist of cohabiting persons without children. The proportion of households consisting of a single woman is the same as that of a single man, around 20 per cent. Women living alone with children make up four per cent of households, and men living alone with children make up two per cent.

Households by type of household, 2023

| Type of household | Number | % |

| Cohabiting without children | 1 176 | 24 |

| Cohabiting with children | 1 004 | 20 |

| Single woman with children | 211 | 4 |

| Single man with children | 79 | 2 |

| Single woman living alone | 1 039 | 21 |

| Single man living alone | 1 010 | 20 |

| Other family households | 414 | 8 |

| Total | 4 932 | 100 |

|---|

There are small differences in the housing situation of girls and boys whose parents do not live together. A slightly higher proportion of boys than girls live roughly equal amounts of time in the homes of both parents, while a slightly higher proportion of girls than boys live only or mostly with their mother. A small proportion of both girls and boys live only or mostly with their father.

Housing situation of girls and boys whose parents do not live together, 2023

Natality

Historically, wars and economic crises are examples of events that have impacted the number of children born. The number of children born is also impacted by the number of women of childbearing age.

The total fertility rate, which is the sum of the average number of births per woman, was 1.5 children per woman in 2023. This is the lowest level measured.

Total fertility rate, 1890–2023

First time parents

In 2023, the average age for becoming a mother was 30 and the average age for becoming a father was 32.

While the childbearing rate is at a historically low level, the average age of new parents has never been higher than 2023. The average age of 30 for mothers and 32 for fathers in 2023 compares with 2000, when the average age of new parents was 28 for mothers and 31 for fathers. Forty years ago, the average age for becoming a mother was 26. The average age for becoming a father was not recorded in 1984.

Source: Population Statistics, Statistics Sweden

That we are having children later in life can be observed in the fact that a greater proportion of both women and men are childless when they are older. This trend has been observed over the course of many years, seen here in comparison with 1970, 1985 and 2000. However, the difference between the proportion of childless women and men is relatively constant, with the proportion of childless men being greater than the proportion of childless women in all age groups.

Childless people born in Sweden by age, 1970, 1985, 2000 and 2023

| Age | 1970 | 1985 | 2000 | 2023 | ||||

| Women | Men | Women | Men | Wommen | Men | women | Men | |

| 25 | 42 | 63 | 62 | 81 | 78 | 89 | 88 | 94 |

| 30 | 20 | 33 | 29 | 48 | 41 | 60 | 57 | 72 |

| 35 | 14 | 23 | 15 | 27 | 20 | 34 | 27 | 42 |

| 40 | 14 | 22 | 13 | 20 | 15 | 26 | 17 | 28 |

| 45 | 16 | 23 | 12 | 18 | 14 | 22 | 13 | 22 |

| 50 | .. | .. | .. | .. | 12 | 19 | 13 | 20 |

Abortions performed

In 2023, around 35,550 abortions were reported. Both the total number of abortions and the number of abortions per 1,000 women of childbearing age have remained relatively constant since the mid-1980s. However, the trend has varied across age groups, shifting from women under the age of 25 to women around the age of 30.

Abortions performed, 1951–2023

The Abortion Act

The Abortion Act (Abortlagen) was introduced in 1975. Under the Abortion Act, a woman has the right to decide to have an abortion up to the 18th week of pregnancy. After that, special authorisation from the Judicial Council of the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare is required.

Source: Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare

Education

Women and men, girls and boys must have the same opportunities and conditions regarding education, study options and personal development.

Gender equality in education is the third gender-equality policy sub-goal. It states that women and men must have equal opportunities and conditions in education, choice of study and personal development.

Schools play an important role in creating an equal society and countering traditional gender patterns. Gender equality in education covers the entire formal education system, from pre-school to adult education, higher vocational education and training, universities and colleges. It also includes education outside the formal system, such as folk high schools and the educational activities of adult educational associations.

Girls and boys, women and men, often study in different programmes, and few programmes have a equal gender distribution. These educational choices affect future careers and thus opportunities for livelihood, independence and empowerment.

Gender equality in schools is not only about educational choices, but also about how girls and boys, women and men, perform, their well-being and their experiences of the school environment.

Child care

The 1970s saw the start of an expansion of publicly funded child care. In 1972, 12 per cent of all children of pre-school age were enrolled in pre-school, educational care or after-school centre. In 2021, the corresponding share was 86 per cent. At the same time, the share of women in the labour force increased significantly in the 1970s and 1980s. (Data for 1972 are for municipalities and data for 2021 are for municipalities and private organisations.)

Preschool, pedagogical care and recreation centres 1972–2023 under municipal management

Grades

Girls, as a group, have higher grades than boys, both in primary and secondary school.

Both girls' and boys' merit ratings in year 9 in primary school have increased over time. In 1998, girls had an average merit rating of 212.0 and boys 190.9. Since then, the merit ratings have increased to 228.4 for girls and 211.6 for boys in 2024. The maximum possible merit rating is 320 points.

Grade point average for pupils who completed the ninth grade, 1998–2021

In both primary and secondary school, students of Swedish heritage have higher grade points than students of foreign heritage. Here, too, there are differences between girls and boys. Girls of Swedish heritage have the highest grades and boys of foreign heritage are the group with the lowest grades.

Spread of grade point average for pupils who completed the ninth grade by Swedish/foreign background, 2021

In upper-secondary education, the maximum possible final school grade is 20. In the 22/23 academic year, girls scored an average of 15.1 points and boys 13.9 points in their final school grade.

Grade points for students in upper secondary school with final grades, by Swedish and foreign background, 2022/23

| Women | Men | |

|---|---|---|

| Swedish background | 15,4 | 14,2 |

| Foreign background | 14,1 | 12,9 |

| Total | 15,1 | 13,9 |

Stress at school

More girls than boys say they are often stressed due to homework or exams. Just over half of girls and a quarter of boys aged 12 to 18 say they are stressed due to homework or exams. This applies to both primary and secondary school.

Children aged 12–18 who state they are often stressed due to homework or tests, 2023

Pupils in upper-secondary schools

In the 22/23 academic year, four national upper-secondary school programmes had an equal gender distribution: Restaurant and Food, Commerce and Administration, Natural Sciences and Economics.

In the 22/23 academic year, 54 per cent of women attended predominately female programmes and 44 per cent of men attended predominately male programmes. 38 per cent of females and 33 per cent of males attended gender-balanced programmes.

Upper secondary school graduates by programme or attachment to programme, 2022/2023

Among pupils with parents who did not complete upper-secondary school, 58 per cent of women and 67 per cent of men of Swedish heritage chose to attend vocational programmes. For students of foreign heritage whose parents had only compulsory education, 34 per cent of women and 48 per cent of men chose vocational programmes.

Among students with parents who have post-secondary education, only 22 per cent of women and 30 per cent of men of Swedish heritage chose a vocational programme. For pupils of foreign heritage, the proportion was even lower: 13 per cent for women and 21 per cent for men.

Pupils in upper secondary school, by programme and parents’ level of educational attainment and Swedish/foreign background, 2023/2024

| Parents with no more than compulsory education | ||||

| Pupils’ programme | Swedish background |

Foreign background |

||

| Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| Higher education preparatory programmes |

43 | 33 | 66 | 53 |

| Vocational programme | 58 | 67 | 34 | 48 |

| Number | 1 350 | 1 360 | 5 960 | 6 040 |

| Parents with no more than upper secondary education | ||||

| Pupils’ programme | Swedish background |

Foreign background |

||

| Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| Higher education preparatory programmes |

51 | 38 | 77 | 64 |

| Vocational programme | 49 | 62 | 23 | 36 |

| Number | 35 000 | 36 300 | 13 320 | 13 500 |

| Parents with post-secondary education | ||||

| Pupils’ programme | Swedish background |

Foreign background |

||

| Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| Higher education preparatory programmes |

79 | 70 | 87 | 79 |

| Vocational programme | 22 | 30 | 13 | 21 |

| Number | 83 480 | 88 190 | 18 980 | 19 890 |

Of the pupils of foreign heritage who commenced upper-secondary studies in 2019, 30 per cent of women and 40 per cent of men have not completed their upper-secondary education. For pupils of Swedish heritage, the corresponding figures are 13 per cent for women and 15 per cent for men.

Pupils who began upper secondary school in the autumn of 2019 and who did not completed their education within four years, by Swedish and foreign background

| Background | Number of enrolments | Percentage failing to complete | ||

| Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| Swedish background | 40 610 | 42 730 | 13 | 15 |

| Foreign background | 14 230 | 16 040 | 30 | 40 |

| Total | 54 870 | 58 800 | 18 | 22 |

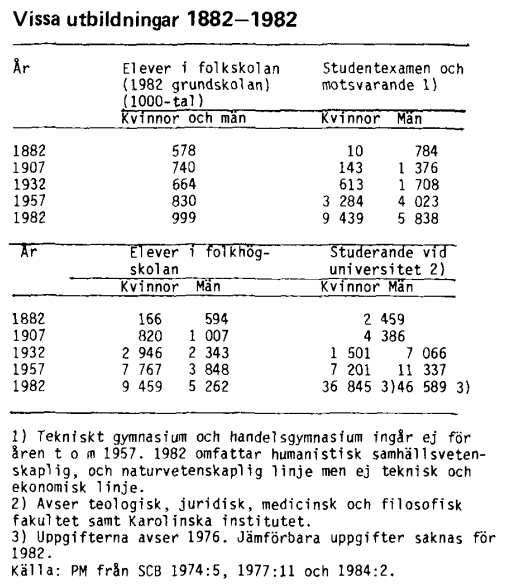

University and college students

There are more women than men studying at universities and colleges. In 1977, a higher-education reform was implemented. It expanded the scope of first-cycle academic education to include teacher and nurse training programmes, among others. As these were predominately female programmes, the reform contributed to a greater proportion of women in higher education than men, and this pattern has continued ever since, with approximately 60 per cent women and 40 per cent men.

Enrolled students academic years, 1977/78–2022/23

The transition from first to second cycle differs between women and men. Of graduates at first- and second-cycle level, a greater proportion of men start a third-cycle programme than women.

In 1986, 24 per cent of doctoral graduates were women and 76 per cent were men. The proportion of women has increased over time, and since 2001 there has been a gender balance among doctoral graduates. As of 2023, half are women and half are men.

Students and graduates from higher education in 1985/86, 1999/00 and 2022//23

| 1985/86 | 1999/00 | 2022/23 | ||||

| Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| Undergraduate and graduate level | ||||||

| Entering higher education | 58 | 42 | 58 | 42 | 58 | 42 |

| Students | 57 | 43 | 59 | 41 | 62 | 38 |

| Graduates | 66 | 34 | 60 | 40 | 64 | 36 |

| Postgraduate level1 | ||||||

| New doctoral students | 31 | 69 | 45 | 55 | 52 | 48 |

| Doctoral students | 30 | 70 | 44 | 56 | 53 | 47 |

| Licentiate degree | 22 | 78 | 37 | 63 | 43 | 57 |

| PhD degree | 24 | 76 | 39 | 61 | 50 | 50 |

Popular education

Women participate in popular education at a much higher rate than men. Sixty-five per cent of participants in popular-education activities in 2023 were women and 35 per cent were men. This pattern is similar for both native and foreign-born women and men. The minimum age for participating in a study circle is 13, but children under 13 can also participate in other popular-education activities.

Participants in popular education by Swedish/foreign background, 2023

Personnel

The gender balance of education-system personnel has long been uneven, with a strong female predominance in early childhood education and a male predominance among university professors. In pre-schools, this imbalance is still evident, with 96 per cent of staff being female and 4 per cent male. However, the gender balance among professors has become slightly more even. As of 2023, women make up 31 per cent of professors, while men make up 69 per cent.

Educational care was also predominately female, with 98 per cent women and 2 per cent men in municipal educational care in 2023. The greatest proportion of men was found among personnel in private after-school centres, where 63 per cent of personnel were women and 37 per cent men.

Staff in preschool, recreation centres and pedagogical childcare, by form of operation, 2023

| Number | Sex distribution | |||

| Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| Municipal preschool | 74 500 | 3 000 | 96 | 4 |

| Preschool under private management | 20 300 | 1 200 | 95 | 5 |

| Municipal recreation centre | 14 100 | 6 500 | 68 | 32 |

| Recreation centre under private man-agement |

1 800 | 1 100 | 63 | 37 |

| Pedagogical childcare under municipal management |

400 | 0 | 98 | 2 |

| Pedagogical childcare under private management |

800 | 0 | 94 | 6 |

In primary and lower-secondary schools, 75 per cent of teachers were female and 25 per cent male in academic year 23/24. Compared to the 85/86 academic year, the proportion of women has increased from 68 per cent, while the proportion of men has decreased from 32 per cent. The gender balance of head teachers has also changed significantly since 85/86. At that time, only 19 per cent of head teachers were women and 81 per cent were men. In academic year 23/24, 73 per cent of head teachers were women and 27 per cent were men.

In upper-secondary schools, the gender balance was even, both among teachers and head teachers. In academic year 23/24, 53 per cent of teachers were women and 47 per cent were men. For head teachers, 57 per cent were women and 43 per cent were men. Upper-secondary schools have also seen major changes since the 1980s, when only 29 per cent of head teachers were women and 71 per cent were men.

Teachers and school leaders in compulsory and upper secondary schools, 1985/86, 2000/01 and 2023/24

| Sex distribution | ||||||

| 1985/86 | 2000/01 | 2023/24 | ||||

| Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| Teachers | ||||||

| Compulsory school | 68 | 32 | 73 | 27 | 75 | 25 |

| Upper secondary school | 44 | 56 | 48 | 52 | 53 | 47 |

| Principals | ||||||

| Compulsory schoo | 19 | 81 | 62 | 38 | 73 | 27 |

| Upper secondary school | 29 | 71 | 34 | 66 | 57 | 43 |

| Other school leaders | ||||||

| Compulsory school | .. | .. | 68 | 32 | 76 | 24 |

| Upper secondary school | .. | .. | 44 | 56 | 61 | 39 |

Among academic staff in higher-education institutions, one third of professors were women and two thirds were men in 2022. This means that there was a significant gender gap at the highest academic level. In contrast, the gender distribution in the other categories of academic staff was even, although there were more men in all but one position. The exception was lecturers, where women accounted for 62 per cent and men 39 per cent in 2022.

Teaching and research staff, by employment category, 2022

Women have always been under-represented among the country's professors, and this employment category still has the lowest proportion of women in higher education. In 2001, the proportion of women among professors was 14 per cent. By 2022, the proportion had increased to 31 per cent.

Professors 2001-2022

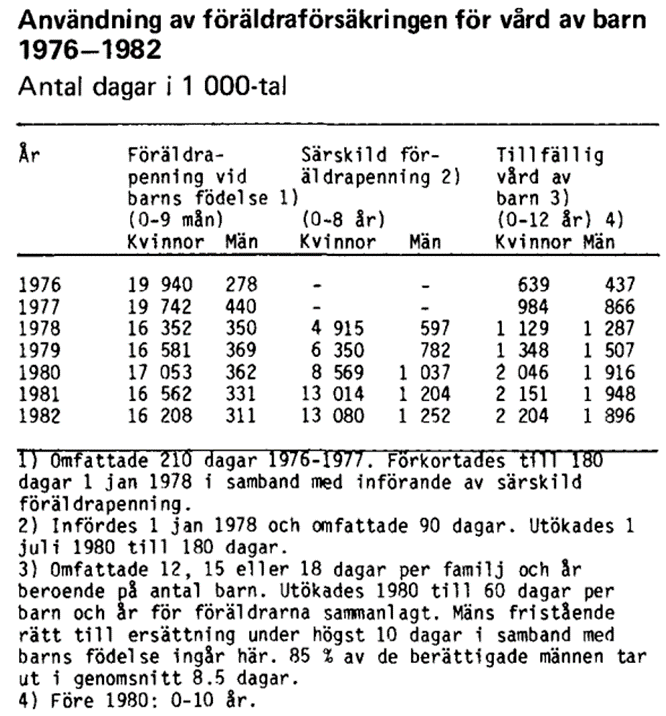

Parental benefit

In 1974, Sweden became the first country in the world to introduce a public parental allowance, enabling both women and men to take time off work to care for their newborn children. This reform replaced the previous maternity insurance and was introduced at the same time as other important gender-equality reforms, such as individual taxation and the expansion of child care. The aim was to increase women's participation in the labour market and to make it possible to combine work with parenthood. The father's role in caring was also emphasised, and, later, children's needs for security and attachment have been highlighted.

Today, the Parental Leave Act gives parents the right to take full leave from work until the child is 18 months old, whether or not they receive parental allowance. Parental leave can be used for continuous periods, single days or parts of days, making it possible to alternate paid and unpaid leave and extend the time at home with the child.

Temporary parental allowance was introduced in 1978 and is often referred to as leave for care of a child, or vab. This permits parents to receive an allowance while staying home from work to care for sick children.

The right to take time off work and receive compensation for lost earnings has been crucial for both women and men to combine work with parenthood. Read more in the chapter Parental Insurance 1974-2024 about the history of parental insurance and how it has developed since its introduction.

In this chapter, we take a closer look at how parental allowance is distributed between women and men.

Parental allowance

After the introduction of the parental allowance in 1974, fathers' take-up was very low, with less than 1 percent of days taken by men. In 1995, the first so-called 'father's month' was introduced, which meant that 30 days were reserved for each parent and could not be transferred. From 2002, 60 days were reserved for each parent, and from 2016 this was increased to 90 days. Men's take-up of parental allowance then increased, to approximately 30 percent around 2016-2017, and has since remained at that level.

Days for which parental beneft is paid, 1974-2023

Women have taken up around 70 percent and men 30 percent of parental-allowance days since 2017, but the total number of parental-allowance days taken up has decreased. Women took up about one fifth fewer parental-allowance days in 2023 compared to 2017, making 2023 the year with the lowest take-up in over 20 years. For men, the decrease is not as large, and men still took up more parental-allowance days in 2023 than ten years ago.

Days for which parental beneft is paid, 1993-2023

Parents take up parental allowance to different extents, depending on the age of the child. The younger the child, the less equal the take-up of parental allowance. For children born in 2015, women took up 88 percent of parental-allowance days and men took up 12 percent during the child's first year of life. During the child's second year, the situation evens out somewhat. At that time, women took up 58 percent and men took up 42 percent.

Not until the child is five years old do women and men take up the same number of parental leave days, on average five days per year.

Days for which parental beneft is paid, by age attained among children born in 2015

| Attained age of child | Number of days | Percentage | |||

| Women | Men | Total | Women | Men | |

| 0 | 8 | 0 | 8 | 100 | 0 |

| 1 | 204 | 27 | 231 | 88 | 12 |

| 2 | 57 | 42 | 98 | 58 | 42 |

| 3 | 12 | 10 | 23 | 55 | 45 |

| 4 | 19 | 17 | 36 | 54 | 46 |

| 5 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 50 | 50 |

| 6 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 48 | 52 |

| 7 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 48 | 52 |

| 8 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 48 | 52 |

| Total | 315 | 111 | 426 | 74 | 26 |

To illustrate how parents take up parental allowance from a child's perspective, the percentage of children whose parents share parental allowance equally is shown. Equal take-up means that the parents have each taken up between 40 and 60 percent of the parental-allowance days when the child turns two.

For children born in 2005, only one in ten children had parents who shared parental benefits equally. This share has slowly increased since then, and for children born in 2021, slightly more than one in five children had parents who shared parental benefits equally.

Proportion of children whose parents have shared parental benefit equally, by year of birth

Care of a sick child (vab)

Women have been taking more care of a sick child days, also known as vab, every year since this option was introduced, in the late 1970s. However, the distribution of vab days has always been more equal than the take-up of parental allowance. For example, in 1980, women took up 95 percent of all parental-allowance days and men 5 percent, while for vab the split was 63 percent for women and 37 percent for men.

In 2023, three out of five vab days were taken up by women and two out of five by men. Since 2015, men's share of vab days has remained just below 40 percent, and in 2021 it reached 40 percent. However, in the last two years, the gender breakdown has fallen back to just below 40 percent for men and just above 60 percent for women.

Days for which temporary parental beneft is paid, 1980–2023

During the pandemic years 2020-2022, the number of days taken for care of a sick child increased to historically high levels, as both women's and men's take-up increased drastically. The gender distribution of vab days remained constant during these years, but due to the large increase in the number of days, the difference in days taken up between women and men grew compared to previous years.

In 2019, before the pandemic restrictions, women took up around 1.5 million more days of leave than men. During the pandemic years 2020-2022, this increased to women taking up on average around 1.8 million more days per year than men.

Days for which temporary parental beneft is paid, 2006-2023

Unpaid household and care work

Women and men must have the same responsibility for unpaid housework and have the opportunity to give and receive care on equal terms.

Equal distribution of unpaid housework and care work is the fourth gender-equality policy sub-goal. The aim of understanding and measuring this work is to shed light on the everyday activities that shape the lives of women and men. This includes everything from cleaning, shopping and car repairs to caring for children, the sick and relatives. By studying who performs these tasks and how much time is spent, a clearer picture of how the workload is distributed in the home can emerge.

Statistics on unpaid labour are often difficult to collect and report. Housework is seen as part of everyday life and differs from paid work in that it is not recorded in any system, but is more or less explicitly distributed among household members. Often it is not even possible to measure the time it takes to perform many of the chores. For example, buying a pair of trousers for children is an activity that can be estimated in terms of time, whereas planning the purchase by comparing prices, researching quality and keeping track of the child's size is an expenditure of time and exercise of responsibility that is more difficult to measure. Caring for an ageing partner, instead of using home-care services, is another example of unpaid domestic work that is difficult to measure; instead we must analyse who actually uses home-care services, in order to form an opinion on who does not.

Statistical surveys measuring unpaid work tend to be expansive and very demanding for participants, often leading to high non-response rates.

Despite such challenges, measuring unpaid housework and care work is important because it is a fundamental part of society. A balanced distribution of unpaid work is therefore crucial to ensure that both women and men have equal opportunities to maintain social contacts, progress in the labour market and engage in voluntary or political activities in their free time.

Caring for children

It is possible to take parental leave without receiving parental allowance. According to the Swedish Social Insurance Agency's model, women are estimated to be on unpaid parental leave for about 33 percent of the time, and men for 27 percent of the time, until their children reach the age of two. In terms of days, this means that women were expected to take an average of 122 days of parental leave without parental allowance and men 36 days.

Days compensated with parental allowance and number of days without parental allowance during parental leave for children aged 0-2 years born in 2021

Time use

Women experience more stress due to being too busy compared to men. This applies whether they are single or cohabiting and whether they have children.

Among single women with children, 41 percent feel stressed because they are too busy. For cohabiting women with children, a slightly smaller proportion, 39 percent, experience stress.

Among single men with children, 28 percent feel stressed because they are too busy, and this is the most stressed group among men. Of men who are cohabiting and have children, 23 percent feel stressed.

Single women without children are more likely to feel stressed than cohabiting men with children.

People aged 20–64 who often feel stressed due to having too much to do by type of household, 2021

Women generally spend more time than men on activities such as cooking, cleaning, washing and caring for their own children (feeding, dressing, hygiene, bedtime). This is the case regardless of women’s income, age, employment status, cohabitant status, or whether they have children. Men generally spend more time than women on gainful employment, home maintenance and repairs and vehicles. For activities such as gardening and grocery-shopping, women and men spend about the same amount of time. This also applies to certain activities linked to their own children, such as helping with homework, attending children's activities, family activities and reading and playing. The time spent on activities related to caring for others also does not differ between genders. In contrast, women spend more time in contact with family and friends than men.

Women aged 18-84 years cook for 1 hour and 24 minutes on average per day. The corresponding figure for men is slightly more than an hour. Cooking also includes baking and setting the table. Women spend more time cleaning than men. On average, women spend 54 minutes per day cleaning compared to 34 minutes for men. Cleaning also includes activities such as washing dishes, making beds, emptying rubbish and tidying up the home. Time use differs between genders in doing laundry. Women do laundry for 25 minutes a day while the corresponding figure for men is 12 minutes. This category also includes other forms of clothing maintenance, such as mending and ironing as well as textile care.

Men spend more time managing household finances. They spend an average of 16 minutes a day on this activity, while women spend 9 minutes.

Source: SCB 2022, En fråga om tid (TID2021) En studie av tidsanvändning bland kvinnor och män 2021

Time spent on unpaid household and care work, by different activities for people aged 20–64, 2021

Gainful employment

Economic gender equality. Women and men must have the same opportunities and conditions for paid work that provide economic independence throughout life.

Economic equality is the second gender-equality policy sub-goal.

Economic equality is influenced by several factors, such as labour-market conditions, education, tax and pension systems, and unpaid housework and care work. Rights such as not having to risk injury or death in the workplace, as well as being protected from sexual assault, are also central to promoting gender equality in the labour market. A job that offers secure and fair conditions enables both women and men to work on equal terms until retirement age.

Women and men work to a large extent in different occupations. Across the labour market, only 23 percent of employed women and 17 percent of employed men worked in gender-balanced occupations in 2022. Women also work part-time to a greater extent than men, take up most of the parental allowance and child care days, and have more sick days than men, which together leads to women working fewer paid hours than men.

This chapter on the labour market contains statistics on the labour market, working hours and self-employment. It also includes statistics on the working environment and statistics on employed persons with disabilities.

Terms

In this section, a number of terms appear that are explained below.

The labour force includes people who are either employed/gainfully employed or unemployed.

Not in the labour force refers to people who are not employed and not looking for work.

Employed refers to people who have gainful employment for at least one hour in the reference week or who have been temporarily absent from work.

Unemployed are individuals who are not employed and who have looked for work and been able to work. People who have got a job that they will start within three months are also counted as unemployed, provided that they had been able to work during the reference week or start work within two weeks thereafter.

The employment rate is the proportion (%) of the population in employment.

Time actually worked is the number of hours a person worked during the reference week.

Hours normally worked is to the working time the person was supposed to work as agreed.

Agreed working time is based on the number of hours a person has as agreed working time.

Absent refers to individuals who have a job, but have not performed that job because of holiday, illness, parental leave, studies, etc.

The economic activity rate is the proportion (%) of the population in the labour force.

The unemployment rate is the proportion (%) of the labour force that is unemployed.

Latent job-seekers refers to people who are able and willing to work, but who have not looked for work. Latent job seekers are not included in the labour force.

The underemployed are people wishing to increase their working hours and who can start to work more.

Since 2005, individuals who are registered in Sweden and work abroad are defined as employed in the Labour Force Surveys. Previously, these individuals were not included in the labour force. Since 2007, individuals who are full-time students and who have looked for work and have been able to work are defined as unemployed. The changes that occurred implied that there were time series breaks, but the tables and figures have been recalculated back to 1987. This is illustrated in the diagrams concerned with a vertical line. In January 2021, the Labour Force Survey was adapted to the EU’s new social statistics regulation, which has caused a break in the time series. These statistics are intended to reflect the labor force and therefore cover the age group 20–64 years up to and including the reference year 2022. From the reference year 2023 onwards, the age group 20-65 years is included. The difference is due to a change in the age limit in the pension system.

Labour market

Population aged 20–65 in and not in the labour force, 2023

There is a clear correlation between level of education and labour-market position, with those who have compulsory education only more often occupying a weaker position. This applies to both native and foreign-born persons and regardless of gender.

Among women aged 25-65 with compulsory education only, slightly more than one in two of those born in Sweden, and around one in three of those born abroad, were employed. At the same time, unemployment, i.e. those willing and able to work, among women with compulsory education only was clearly higher among foreign-born women. Among men with compulsory education only, employment is higher than among women.

Eight out of ten men born in Sweden were in employment, and around half of men born abroad. As with women, foreign-born men were more likely to be unemployed than native-born men. However, the comparison is affected by the fact that the foreign-born are on average younger than the native-born.

Employment, unemployment and activity rate among people aged 25–65 by level of educational attainment and Swedish/foreign-born, 2023

| Level of educational attainment |

Employment rate1 |

Unemployment rate2 |

Economic activity rate3 |

|||

| Born in Sweden |

Born abroad |

Born in Sweden |

Born abroad |

Born in Sweden |

Born abroad |

|

| Women | ||||||

| Compulsory | 58 | 36 | .. | 41 | 65 | 62 |

| Upper secondary | 79 | 68 | 3 | 16 | 82 | 81 |

| Post-secondary | 81 | 2 | 10 | 92 | 89 | |

| n/a | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| All | 86 | 70 | 3 | 15 | 88 | 83 |

| Men | ||||||

| Compulsory | 73 | 66 | 6 | 24 | 78 | 87 |

| Upper secondary | 87 | 79 | 3 | 14 | 90 | 92 |

| Post-secondary | 91 | 88 | 2 | 8 | 93 | 95 |

| n/a | .. | 75 | .. | .. | .. | 84 |

| All | 88 | 81 | 3 | 12 | 91 | 93 |

The percentage of women in the labour force rose sharply in the 1970s and 1980s. A large part of this increase can be explained by an increase in women with long part-time employment. In the 1990s, the percentage of people unemployed increased and, to a certain extent, so did the percentage of women outside the labour force. Unemployment had decreased once more in the early 2000s, but the proportion of unemployed women remained higher than in the 1970s and 1980s. Roughly explained, and with variations over the years, the proportion of women with full-time employment has continued to rise. At the same time, the proportion of women aged 20–64 in the population with part-time employment has dropped in recent decades.

Women aged 20–64 by labour force status and hours normally worked, 1970–2020

The percentage of men in the labour force was essentially constant in the 1970s and the 1980s. In the 1990s, the unemployment rate rose among men, while the percentage of men outside the labour force also increased slightly. In the early 2000s, the percentage of unemployed men had decreased, although the percentage of those unemployed remained higher than in the 1970s and 1980s. The percentage of men working full-time or part-time has not changed signifIcantly in recent years. However, considering the trend in the most recent decades, the percentage of men working part-time has increased slightly.

Men aged 20–64 by labour force status and hours normally worked, 1970–2020

Due to changes in the Labour Force Surveys, labour-force participation in 2023 is reported for agreed time, instead of hours normally worked.

Labour force status and agreed working time among people aged 20-65, 2023

| Women | Men | |

|---|---|---|

| Full-time 35- hours | 61 | 74 |

| Long part-time 20-34 hours | 12 | 6 |

| Short part-time 1-19 hours | 4 | 2 |

| Unemployed | 6 | 6 |

| Not in the labour force | 15 | 10 |

Percentage of population in the labour force and percentage of labour force unemployed

The percentage of population in the labour force is the proportion of the labour force that is employed, and the percentage of labour force unemployed is the proportion of the labour force that is unemployed. In 2023, the percentage of population in the labour force for the 20-65 age group was 85.2 percent for women and 89.9 percent for men. The percentage of labour force unemployed for the same age group was 6.7 percent for women and 6.4 percent for men.

The percentage of labour force unemployed for women and men follow broadly similar patterns over time. In both groups, unemployment increased during the economic crisis of the 1990s and has not returned to the lower levels of previous years since then. Among both women and men, the percentage of labour force unemployed is highest at younger ages.

Relative unemployment rate among women by age, 1970–2023

Relative unemployment rate among men by age, 1970–2023

Opportunity to work from home

Across all sectors, men and women work from home about equally. In terms of sectors, working from home is most common in the public sector. In 2023, more women in the public sector worked from home to some extent, 64 percent, compared to 49 percent of men. In the private and municipal sectors, the differences between women and men's opportunities to work at home are small.

The occupations where working from home was most common in 2023 were managerial occupations. Eighteen percent of managers worked from home at least half of their working days, and 43 percent said they worked from home for less than half of those days. About the same proportion of women as men in managerial occupations worked from home.

Source: Labour Force Survey (LFS), published in Women and men in Sweden 2024, Statistics Sweden

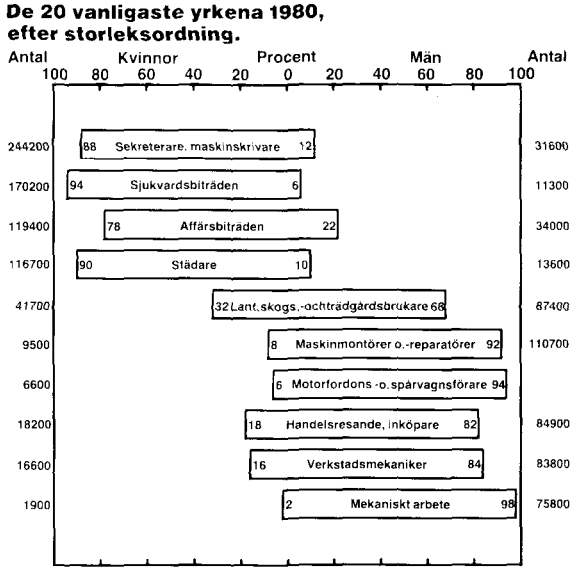

Gender breakdown of the labour market

Among the 30 largest occupations five had an equal sex distribution; that is, there were 40–60 percent women and 40–60 percent men. These were: Management and organisation

developers Cooks and cold-buffet staff, Restaurant and kitchen workers, etc, Customer service staff and Shop sales, speciality stores.

The most female-dominated occupation out of the 30 largest occupations in 2022 was Preschool teachers, with 96 percent women and 4 percent men. The most male-dominated

occupation was Woodworkers, carpenters, etc. with 2 percent women and 98 percent men.

The 30 largest occupations, 2022

In 2022, 23 percent of employed women and 17 percent of employed men were working in gender-balanced occupations in the labour market as a whole.

Both women and men were most likely to work in occupations where their own sex predominated, with 62 percent of women working in predominately female occupations and 64 percent of men working in predominately male occupations. Slightly more men worked in predominately female occupations than women worked in predominately male occupations.

Employees by sex distribution in the occupation, 2022

| Occupations with | Women | Men |

| 90-100 % w, 0-10 % m |

11 | 1 |

| 60-90 % w, 10-40 % m |

51 | 18 |

| 40-60 % w, 40-60 % m |

23 | 17 |

| 10-40 % w, 60-90 % m |

14 | 45 |

| 0-10 % w, 90-100 % m |

1 | 19 |

| All | 100 | 100 |

Under 1970- och 1980-talen ökade antalet kvinnor på arbetsmarknaden. Detta framförallt till följd av att antalet kvinnor i kommunal sektor fördubblades. Under 1980- och 1990-talen arbetade ungefär lika många kvinnor i kommunal som i privat sektor. Idag arbetar dock den största andelen av kvinnorna i privat sektor. Under hela tidsperioden har män till största delen arbetat i privat sektor. Minskningen i statlig sektor beror delvis på personalminskningar men också på bolagiseringen av flera statliga verk under 1990-talet. Anställda där räknas därefter in i privat sektor.

Employed women aged 20–64 by sector, 1970–2020

Employed men aged 20–64, by sector, 1970–2023

Working hours

More women than men work part-time. Twenty-six percent of women and 11 percent of men in employment aged 20-65 worked part-time in 2023.

Employed people aged 20–65 who work full-time and part-time, 2023

Reasons for part-time work among people aged 20–65, 2023

For employed men who have children, the differences in working hours are not so great. Most of them work full-time, no matter how old their children are or how many children they have. But for women it is different. Even with one child, more women work part-time than men. For women with three children, over 36 percent work part-time when the youngest child is 1-2 years old. Even when the youngest child is between 11 and 16 years old, women with three children are more likely to work part-time compared to women with fewer children.

Employed parents aged 20–65 with children at home aged 16 years and younger, by number of children, the youngest child’s age and length of working hours, 2023

| Number of children | Women | Men | ||

| Youngest child’s age | Full time |

Part time |

Full time |

Part time |

| 1 child | ||||

| 0 years | 85 | .. | 91 | .. |

| 1-2 years | 71 | 29 | 89 | 11 |

| 3-5 years | 71 | 29 | 91 | 9 |

| 6-10 years | 78 | 22 | 95 | .. |

| 11-16 years | 81 | 19 | 94 | 6 |

| 2 children | ||||

| 0 years | 75 | 25 | 91 | .. |

| 1-2 years | 67 | 33 | 92 | 8 |

| 3-5 years | 71 | 29 | 91 | 9 |

| 6-10 years | 74 | 26 | 94 | 6 |

| 11-16 years | 79 | 21 | 96 | 5 |

| 3 children or more | ||||

| 0 years | 78 | .. | 91 | .. |

| 1-2 years | 64 | 36 | 92 | .. |

| 3-5 years | 69 | 31 | 94 | .. |

| 6-10 years | 74 | 26 | 95 | .. |

| 11-16 years | 75 | .. | 92 | .. |

Holidays were the most common reason for whole-week absences for women as well as men without children. However, a different pattern emerges for women and men with children under age 7. Among men, holidays are still the most common reason, but among women it is child care.

Employed people aged 20–64 who have been absent the entire week, by reason, 2023

| Women, all | Men, all | Women with children under age 7 | Men with children under age 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sick | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| Holiday | 9 | 8 | 8 | 9 |

| Care of children | 4 | 1 | 17 | 6 |

| Other | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 18 | 13 | 29 | 17 |

Flexible working hours

Around 64 percent of women say that they can control their working hours to some extent, which is less than among men, where the corresponding proportion is 76 percent. The degree of flexibility varies to a great extent depending on sector, occupation and industry.

Approximately 88 percent of employees in the public sector report that they can fully or partially control their working hours, which is more than in the municipal and private sectors, where the corresponding proportion is 55 percent and 68 percent respectively. Employees in occupations requiring higher education are more likely to say that they have full or partial control over their working hours.

Source: Labour Force Survey (LFS), published in Women and men in Sweden 2024, Statistics Sweden

Working environment

When a serious injury or death occurs at a workplace, the employer is obliged, under the Work Environment Act, to report it to the Swedish Work Environment Authority. Work-related injuries affecting several workers at the same time and incidents involving serious risk to life or health must also be reported. The latter category also includes events that have affected someone psychologically, for example if someone has been exposed to harmful stress for a long time and reacted strongly to it.

More information is available from

the Swedish Work Environment Authority.

Reports of work-related illness are more likely to involve women, while men are more likely to suffer accidents leading to sickness absence and death. Most reports of occupational accidents resulting in sickness absence concern young men aged 20 to 24.

In 2023, the number of reported occupational accidents resulting in sickness absence per 1,000 employed persons aged 20 to 24 was 14.5 for men and 10.1 for women. The Swedish Work Environment Authority emphasises that some of the reasons may include poor training and lack of knowledge regarding the importance of work-environment factors.

Source: Fokus på ungas arbetsmiljö, Swedish Work Environment Authority

Reported occupational injuries among employed persons, 2023

| Women | Men | |

|---|---|---|

| Occupational diseases | 12 141 | 4 890 |

| Occupational accidents with sick leave | 15 740 | 21 812 |

| Occupational accidents without sick leave | 37 926 | 34 009 |

| Fatal workplace accidents | 9 | 31 |

Significantly more men than women die in occupational accidents. Over time, deaths among men have declined sharply, while deaths among women have remained relatively constant.

Deaths in occupational accidents, 1955-2023

The Work Environment Survey monitors working conditions in the Swedish labour market. Women are more likely than men to report problems with insomnia, headaches and overwork. Men are more likely to report being exposed to noise, working when they should be on sick leave and doing heavy lifting every day.

Work environment conditions for employed persons aged 20–64, 2021

It is mainly young women aged 16-20 who have been sexually harassed at work at least once in the last 12 months. They are most likely to be victimised by people not employed at their workplace, such as customers, clients, passengers or students.

Subjection to sexual harassment at least once in the past 12 months by age, 2021

Disability

Approximately 14 percent of all employed women and just under 10 percent of all employed men experience discrimination in the workplace. More women than men report having been subjected to violence or threats of violence at least once in the past 12 months: slightly less than a fifth of women and slightly less than a tenth of men.

The statistics for women and men with reduced work capacity due to disability are subject to some uncertainty, but there is a tendency for a higher proportion of women with reduced work capacity to have experienced threats or intimidation in the last 12 months compared to men with reduced work capacity.

Employed persons aged 20-64 years who have experienced violence, threats of violence or personal persecution, by disability and work capacity, 2021

Over 90 percent of women with reduced work capacity due to disability have worked despite illness. More than 70 percent of men in the same group say they have worked despite illness. This is a higher proportion for both women and men compared to all persons in employment.

Among women with reduced work capacity due to disability, 21 percent report working despite illness because they were afraid of losing their job. The corresponding share for men in the same group is 7 percent. Slightly less than two-thirds of women with reduced work capacity report working despite illness because they cannot afford to be ill. The corresponding share for men with reduced work capacity is one third.

Persons with/without disability aged 20-64 who worked at any time in the last 12 months despite illness 2021

| All employed | Persons with disability with reduced work capacity | |||

| Women | Men | Women | Men | |

Worked despite illness |

63 | 52 | 93 | 72 |

| Reason: | ||||

Fears dismissal |

13 | 10 | 21 | 7 |

| Can not afford to be sick | 29 | 21 | 63 | 29 |

One in five women with a disability has fixed-term employment, a slightly higher proportion than men with disabilities. Men without disabilities have the lowest share of fixed-term contracts. Among employed women and men without disabilities, 86 and 88 percent respectively have permanent employment.

Employed persons with/without disability aged 16-65 years by type of employment

Entrepreneurship

More men than women are self-employed. In 2022, approximately 30 percent were women and 70 percent were men. Among women, being self-employed is most common in business services and personal and cultural services etc. Business services are also most common among men, along with the construction industry.

Self-employed, 20 years and older, by industry, 2022

| Number | Percentage distribution | Sex distribution | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| Personal and cultural services, etc. |

39 | 65 | 20 | 5 | 62 | 38 |

| Health and social care | 32 | 20 | 7 | 2 | 61 | 39 |

| Education | 15 | 40 | 4 | 1 | 56 | 44 |

| Corporate services | 14 | 47 | 25 | 18 | 37 | 63 |

| Hotels and restaurants | 11 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 32 | 68 |

Real estate companies |

6 | 13 | 2 | 2 | 31 | 69 |

| Commerce | 6 | 5 | 10 | 11 | 27 | 73 |

| Agriculture, forestry and fishery | 5 | 22 | 9 | 13 | 23 | 77 |

| Manufacturing, mining and quarrying |

5 | 28 | 3 | 6 | 20 | 80 |

| Information and communication |

4 | 69 | 3 | 8 | 15 | 85 |

| Transport companies | 3 | 8 | 1 | 5 | 7 | 93 |

| Construction industry | 1 | 18 | 3 | 19 | 5 | 95 |

Other industries |

1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 18 | 82 |

Unknown industry |

14 | 17 | 9 | 5 | 44 | 56 |

| Total | 156 | 362 | 100 | 100 | 30 | 70 |

If one does not include cases in which the industry is unknown, the only industry with an even gender breakdown of self-employed persons is Educational system. Of the other industries, Personal and cultural services, etc., and Health and community care services are predominately female, while the rest are predominately male.

Self-employed, 20 years and older, by industry, 2022

Business operators 20 years and older by number of employees at company and legal form of company, 2022

| Number of gainfully employed |

Women | Men | ||

| Business operator in own limited co |

Selfemployed | Business operator in own limited co |

Selfemployed | |

| 1 | 39 | 66 | 33 | 57 |

| 2-4 | 29 | 5 | 29 | 7 |

| 5-9 | 13 | 1 | 15 | 1 |

| 10-19 | 7 | 0 | 9 | 0 |

| 20-49 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| 50- | 4 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Totalt percent | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Number | 64 | 92 | 199 | 163 |

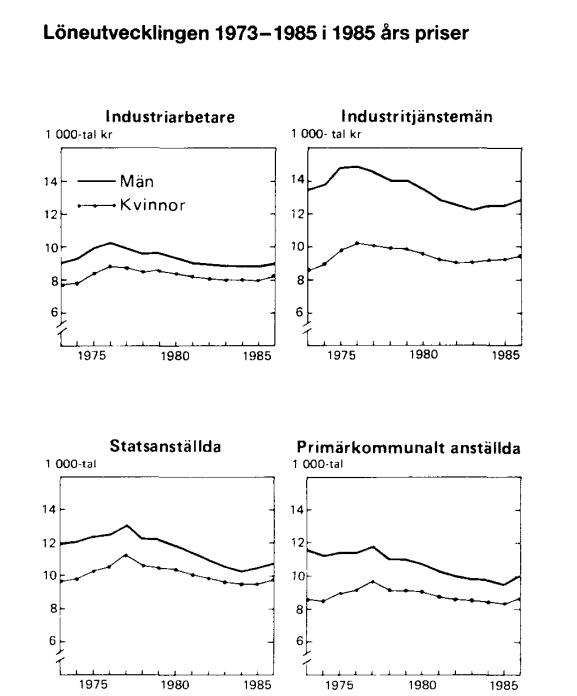

Wages and salaries

Economic gender equality. Women and men must have the same opportunities and conditions for paid work that provide economic independence throughout life.

Economic equality is the second gender-equality policy sub-goal. Economic equality is influenced by several factors, such as labour-market conditions, education, tax and pension systems, and unpaid housework and care work. Statistics highlighting economic equality can also be found in the chapters on education, parental insurance, unpaid housework and care work, gainful employment and income.

This chapter takes a look at wages and salaries and the gender wage differentials. It is important to distinguish between wages or salary and income. Wages and salaries are defined as remuneration for work performed during a given unit of time, while income is a broader term that includes other types of income in addition to wages and salaries.

The Swedish National Mediation Office is tasked with monitoring the gender wage differentials. They state that the main reason for gender wage differentials is that women and men largely work in different occupations with different salary levels. The different size of the wage differential in different sectors is another contributing factor. It is highest in the regions and lowest in the municipalities. The average monthly wage across the entire labour market in 2023 was SEK 37,800 for women and SEK 42,000 for men.

Wage differentials

The gender wage differential is lowest in municipalities and highest in the regions. Since 1987, the gender wage differential has narrowed in all sectors. Across all sectors, women earned 90 percent of men's wages in 2023. Standard weighting can take into account that women and men have different ages, education, working hours, occupy different sectors and belong to different occupational groups. Any wage differential that remains after standard weighting cannot be explained by statistical methods. In 2023, women's share of men's wages after standard weighting was 95 percent.

Women’s pay as a percentage of men’s, by sector, 1994–2023

| Year | Municipality | County council |

Central government |

Private sector |

All sectors | |||||

| Unweighted | Weighted | Unweighted | Weighted | Unweighted | Weighted | Unweighted | Weighted | Unweighted | Weighted | |

| 1994 | 86 | . | 74 | . | 83 | . | 85 | . | 84 | . |

| 1996 | 87 | 98 | 71 | 94 | 83 | 93 | 85 | 91 | 83 | 92 |

| 1998 | 89 | 98 | 71 | 93 | 84 | 92 | 83 | 90 | 82 | 91 |

| 2000 | 90 | 98 | 71 | 93 | 84 | 92 | 84 | 90 | 82 | 92 |

| 2002 | 90 | 98 | 71 | 92 | 84 | 92 | 85 | 90 | 83 | 92 |

| 2004 | 91 | 98 | 71 | 93 | 85 | 92 | 85 | 91 | 84 | 92 |

| 2006 | 92 | 98 | 72 | 93 | 87 | 93 | 86 | 91 | 84 | 92 |

| 2008 | 92 | 99 | 73 | 93 | 88 | 93 | 86 | 91 | 84 | 92 |

| 2010 | 94 | 99 | 73 | 94 | 89 | 94 | 87 | 92 | 86 | 93 |

| 2012 | 94 | 99 | 75 | 94 | 91 | 94 | 88 | 92 | 86 | 93 |

| 2014 | 95 | 99 | 76 | 95 | 92 | 94 | 88 | 93 | 87 | 94 |

| 2015 | 95 | 99 | 78 | 95 | 93 | 95 | 88 | 93 | 87 | 94 |

| 2016 | 97 | 99 | 79 | 95 | 93 | 95 | 88 | 94 | 88 | 95 |

| 2017 | 97 | 99 | 79 | 95 | 93 | 95 | 89 | 94 | 89 | 95 |

| 2018 | 97 | 99 | 80 | 95 | 93 | 95 | 90 | 94 | 89 | 95 |

| 2019 | 98 | 99 | 81 | 96 | 94 | 95 | 91 | 94 | 90 | 95 |

| 2020 | 98 | 99 | 82 | 96 | 94 | 95 | 90 | 94 | 90 | 95 |

| 2021 | 98 | 99 | 82 | 96 | 95 | 95 | 90 | 94 | 90 | 95 |

| 2022 | 99 | 99 | 83 | 96 | 95 | 96 | 90 | 93 | 90 | 95 |

| 2023 | 99 | 99 | 82 | 96 | 94 | 95 | 91 | 93 | 90 | 95 |

Women’s pay as a percentage of men’ all sectors, 1994-2023

Between 2005 and 2023, the unweighted wage differential between men and women has narrowed by 6.4 percentage points. However, as of 2019, the gender wage gap has remained largely unchanged.

Development of the wage gap between women and men, 2005-2023

Wage distribution

Women's wage distribution in occupations requiring higher education is smaller than the distribution for men. This means that men's wages vary more within occupational areas. In all occupations requiring higher education, men's median is higher than women's. The median is the value that 50 percent of the group is below and 50 percent of the group is above. The highest distribution among both women and men in 2023 was in Managerial work in the private sector.

Wage dispersion in occupational groups that require higher education, 2023

The wage distribution for both women and men is smaller for occupations that do not normally require higher education and, in general, the differences between women and men are smaller than among occupations that do require higher education.

Wage dispersion by occupational groups that do not normally require higher education, 2023

Wages in different occupational groups

In the ten largest occupational groups in 2023, men had higher average earnings than women in seven out of ten groups. In the three occupations where women earned more than men, the difference was small, between SEK 200 and 400 per month. In the occupations where men earned more than women, the difference in average pay for one occupation was only SEK 100 a month, but in the other six occupations the difference was much greater, between SEK 1,100 and SEK 6,900.

Average salary in the ten most common occupational groups in 2023

| Occupational group | Number | Sex distribution | Sex distr. Average salary (SEK) |

Women's salaries as a % of men’s salaries |

|||

| Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | ||

| Shop staff | 135 | 86 | 61 | 39 | 31 900 | 33 000 | 97 |

| Primary and preschool teachers |

156 | 38 | 81 | 19 | 36 900 | 37 000 | 100 |

| Attendants, care providers and personal care assistants, etc. |

134 | 57 | 70 | 30 | 30 900 | 30 700 | 101 |

| ICT architects, system developers and test managers |

44 | 131 | 25 | 75 | 50 500 | 53 900 | 94 |

| Office staff and secretaries |

139 | 28 | 83 | 17 | 34 700 | 36 400 | 95 |

| Assistant nurses | 144 | 21 | 87 | 13 | 32 100 | 31 700 | 102 |

| Organisation developers, analysts and HR specialists, etc. |

87 | 51 | 63 | 37 | 46 300 | 53 200 | 87 |

| Insurance advisors, sales and purchasing agents, etc |

50 | 85 | 37 | 63 | 43 700 | 50 200 | 87 |

| Childcare workers and student assistants, etc. |

103 | 20 | 84 | 16 | 26 900 | 26 700 | 101 |

| Engineers and technicians | 26 | 97 | 21 | 79 | 44 500 | 46 900 | 95 |

In the ten most common occupational groups, 45 percent of all employees are women and 26 percent of all employees are men.

Average salary in the ten most common occupational groups in 2023

Seven of the ten largest occupational groups are predominately female and three are predominately male. None of the occupational groups has an even sex distrubution.

Sex distribution The ten most common occupational groups in 2023

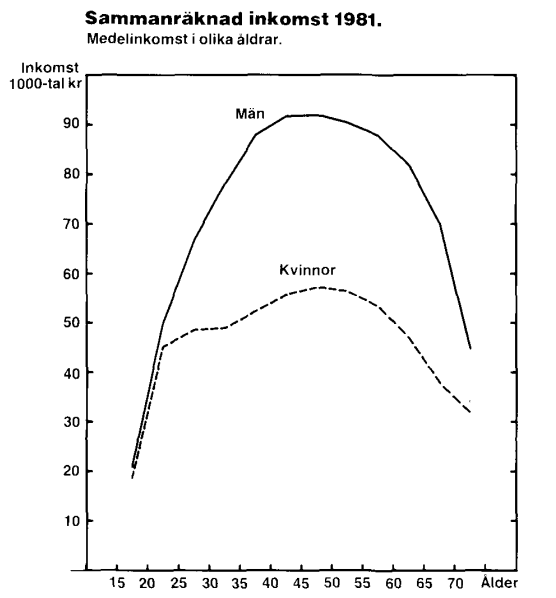

Income

Women and men must have the same opportunities and conditions for paid work that provide economic independence throughout life.

Economic equality is the second gender-equality policy sub-goal. Economic equality is influenced by several factors, such as labour-market conditions, education, tax and pension systems, and unpaid housework and care work. Statistics highlighting economic equality can also be found in the chapters on education, parental insurance, unpaid housework and care work, gainful employment and wages.

Income is a broader term than wages and salary and also includes other income. This chapter takes a look at income and how it is broken down between women and men.

What is a wage and what is income in the statistics?

Wages and salary are distinct from income.

Wages and salary are compensation for work performed. In statistics on wages and salary, wages and salary are usually reported as 'monthly wages'. In this case, hourly and part-time wages have been converted to full-time wages for comparability. Thus, in the statistics, wages and salaries are not affected by, for example, absences, part-time work or overtime.

Income is defined more broadly than wages and salary. What is included depends on how income is defined, but in addition to income from labour, it can include, for example, pensions, social insurance benefits, means-tested benefits and capital income. Income statistics usually refer to annual income, which is affected by factors such as wage levels, absences from work, overtime, etc.

Earned income

Among single as well as cohabiting women and men, people in their fifties have the highest total earned income. Total earned income is lower among women and men in their twenties and among the elderly, especially among those aged 70 and over, whose income consists mostly of pensions.

Cohabiting men have the highest total earned income in all age groups, except among the very oldest. Among the very youngest women and those in their forties and fifties, cohabiting women have a higher total earned income than single women. Among women over 70 years of age, single persons have a higher total earned income than cohabitants.

Total earned income for cohabiting adults/single people, by age, 2022

Men have a higher total earned income compared to women in all age groups between 20 and 64, and this applies whether or not they have children living at home aged 0-19 years. The difference in total earned income is greater between women and men with children compared to women and men without children. This is the case in the age groups up to around 60, and thereafter women and men without children have a higher total earned income. However, the number of individuals with children aged 0-19 living at home is low in higher age groups, so that the differences in these groups are based on a smaller population and should be interpreted with some caution.

Another pattern that emerges is that women in their 30s without children have a higher total earned income than women with children in the same age group. In the age groups 40 years and older, the relationship is inverted. Men with children in the age groups 30 years and older have a higher total earned income compared to men without children.

Total earned income for persons with or without children aged 0-19, by age, 2022

Incomes have increased every year in the 2000s, with the exception of 2022, when incomes fell in real terms compared to previous years, due to inflation. Women's income measured as a share of men's income has also increased gradually throughout the 2000s. This applies to both earned and net income, and to the lower as well as the upper portions of the income scale. The same trend also applies to earlier periods, although statistics before 2000 are not fully comparable with later years' data.

Dispersion of total earned income among individuals aged 20–64 in 2000, 2010 and 2022

Dispersion of net income for individuals aged 20–64 in 2000, 2010 and 2022

Permanent low or high income means being in the same income group for six consecutive years. The income groups are created by dividing the population into five equal groups (quintiles), with the fifth and lowest income group in quintile 1 and the highest income group in quintile 5.

A greater share of women than men aged 20-64 have permanent low income. However, the difference between women and men has diminished over time. In 2005, the first year of measurement, there was an eight per cent difference between women and men who were permanently in the lowest income group. At the same time as gender gaps have narrowed, the share of permanent low income has increased for both women and men.

Persons aged 20-64 with persistently low/high income 2005-2022

To enable comparisons of disposable income between different types of households, an economic standard is used to relate the household’s total disposable income to the household composition of adults and children. In 2022, single women with children had the lowest economic standard. Economic standards were also lower in households with several children compared to households with one child. This was the case for cohabiting households as well as households with single men and single women.

Economic standard for individuals aged 20-64, by household type, 2022

| Type of household | Median income |

| Cohabiting | |

| without children | 421 |

| with children 0-19 years | 304 |

| of whom with one child | 335 |

| with two children | 305 |

| with three children or more | 245 |

| Single women | |

| without children | 266 |

| with children 0-19 years | 206 |

| of whom with one child | 223 |

| with two children or more | 192 |

| Single men | |

| without children | 285 |

| with children 0-19 years | 249 |

| of whom with one child | 264 |

| with two children or more | 234 |

In Sweden, slightly less than four per cent of households have received social assistance or introduction benefit. Single men without children are the most common household receiving social assistance and make up two-fifths of all households receiving social assistance. In terms of household type, however, the greatest proportion of households consisting of single women with children receive social assistance, at 11 per cent.

Households receiving financial assistance, by type of household, with applicants aged 18–64, 2023

| Type of household | Number | Proportion of everyone in each group |

Percentage distribution between household types |

| Cohabiting without children | 4 300 | 1 | 3 |

| Cohabiting with children | 13 400 | 1 | 10 |

| Single women without children | 37 400 | 5 | 27 |

| Single women with children | 21 100 | 11 | 15 |

| Single men without children | 57 700 | 6 | 42 |

| Single men with children | 3 700 | 6 | 3 |

| Total | 137 600 | 4 | 100 |

Pension and income for people aged 65 and over

The amount of pension you receive depends on several factors. Simply put, the higher your salary and the more you work, the higher your pension.

Women are on average paid less than men. This wage differential is largely due to the fact that women and men work with different things and in different sectors. Women also work part-time to a greater degree than men, take the majority of parental leave and childcare days and have more sick days. All this leads to women having less income than men, resulting in a lower pension at the end of their working life.

In 2022, women's share of men's pensions was 75 percent and the difference increases with age. In the oldest age group, 85-89 years, women's pensions were 67 percent of men's and in the youngest age group, 65-69, they were 77 percent.

Women’s pensions as a percentage of men’s pensions (average value), by age, 2004–2022

People aged 65 and older, by type of pension, 2022

| Type of pension | Number of people with a pension |

Pension, median value |

Proportion with type of pension |

Women’s pension as a % of men’s pension (median value) |

|||

| Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | ||

| Total with some kind of pension |

1 123 | 985 | 197 | 261 | 98 | 98 | 75 |

| Of whom with | |||||||

| National pension | 1 111 | 970 | 160 | 200 | 97 | 97 | 80 |

| Of whom with minimum pension |

700 | 228 | 10 | 8 | 61 | 23 | 133 |

| Occupational pension |

995 | 886 | 32 | 56 | 87 | 88 | 57 |

| Private pension | 298 | 279 | 24 | 31 | 26 | 28 | 80 |

Among those aged 65 and over, single women have higher net incomes than cohabiting women. For men, on the contrary, the net income of single people is lower than that of cohabiting people.

Among those aged 65 and over, cohabiting women have a smaller share of men's net income than women living alone. In 2022, single women's share was 90 percent of men's net income, while cohabiting women's share was 73 percent.

Net income for people aged 65 and older, by type of household and age, 2022

| Single | |||||

| Age | Women | Men | Women’s share of men’s net income |

Number | |

| Women | Men | ||||

| 65‑69 | 244 | 261 | 93 | 86 | 71 |

| 70‑74 | 199 | 213 | 93 | 95 | 66 |

| 75‑79 | 192 | 209 | 92 | 110 | 64 |

| 80‑84 | 189 | 209 | 90 | 92 | 42 |

| 85- år | 186 | 208 | 89 | 131 | 43 |

| Total | 194 | 216 | 90 | 514 | 286 |

| Cohabiting | |||||

| 65‑69 | 239 | 340 | 70 | 157 | 165 |

| 70‑74 | 185 | 256 | 72 | 151 | 164 |

| 75‑79 | 165 | 225 | 73 | 131 | 155 |

| 80‑84 | 157 | 216 | 73 | 63 | 88 |